Nigeria is home to one of the world’s largest populations of people living with HIV. And while health care workers in the country are often strapped for resources and don’t have access to the latest medications, they have made significant progress in the fight against the virus, according to Phyllis Kanki, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

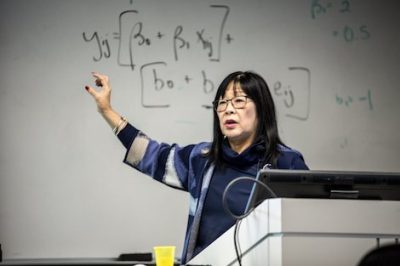

To celebrate World AIDS Day, the Harvard Chan School’s Nigerian Student Association hosted a discussion on December 3, 2018, with Kanki, who has spent nearly 20 years working on the epidemic in Nigeria. In 2000, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation awarded Kanki a $25 million grant that she used to help establish the AIDS Prevention Initiative in Nigeria. Not long after came the launch of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the groundbreaking effort to rapidly expand access to HIV treatments in high-burden countries.

At the time, Kanki told attendees, only the sickest patients were receiving treatment and the infrastructure and tools needed to address the disease were sorely lacking in much of the developing world. Nigeria was no exception. “Up until that point, treatment in Nigeria was really only accessible to people who had the resources to go to Europe to get the drugs,” she said.

After securing the Gates Foundation grant and PEPFAR funding, Kanki and her colleagues pursued a multi-pronged approach to tackling the epidemic in Nigeria. They partnered with local university teaching hospitals to improve access to treatment, scaled-up HIV testing and counseling services, established programs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of the virus, built laboratory capacity, designed training manuals and programs for health care workers, introduced technologies to monitor drug-resistance, and, importantly, set up an electronic medical records (EMR) system that could quickly and cleanly capture crucial data.

The EMR didn’t only help health care workers on the ground monitor the progress of patients, it was instrumental in fulfilling PEPFAR’s stringent reporting requirements and securing future funding. “We had to file reports every quarter and then ever month,” she said, noting that strong data are critical to the federal legislators who hold the purse strings of PEPFAR.

All the efforts paid off. Dozens of sites around the country started providing services to prevent mother-to-child transmission and access to antiretroviral drugs, and by 2013, 160,000 Nigerians had received HIV treatment through the PEPFAR programs Kanki helped manage.

Yet plenty of challenges remain today. More than 3 million people in Nigeria are still living with HIV and an estimated 1.5 million to 2 million are still in need of drugs. Moreover, Kanki said that clinicians in the country today have to work with “a shallow pharmacy shelf.” In other words, newer, costlier drugs aren’t widely available in the country and patients are left taking less effective regimens that have been in use for many years. Among the problems this poses it that it increases the risk of patients developing and spreading drug-resistant strains of the virus.

Lastly, Kanki noted that their work in Nigeria produced significant research findings. More than 150 peer-reviewed studies and reports on their work in Nigeria have been published as of 2018. And Kanki told attendees that a new book she co-authored, Turning the Tide: AIDS in Nigeria, will be released early next year that examines the last decade of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Nigeria.

–Chris Sweeney

Culled from hsph.harvard.edu